(above) Photograph, c.1884-85, of bridge walkway and High Bridge Reservoir and Tower. Below them, to the right, are the powerhouse and its smokestack, also seen in the [following illustration]. (Collection of NYC Municipal Archives; courtesy of C. Fahn)

My interest in the Old Croton Aqueduct began when I became fascinated by the history of my village, Croton-on-Hudson, and started collecting old prints, postcards, maps and other antiquarian materials that bore the name "Croton" in their titles. It turned out that almost all such prints had to do with the Old Croton Aqueduct as Croton itself had been a sleepy hamlet in the 19th century, nestled between those well-documented villages Peekskill and Sing Sing, but unlike them, not much of a magnet for the artists of the Hudson River School of painting.

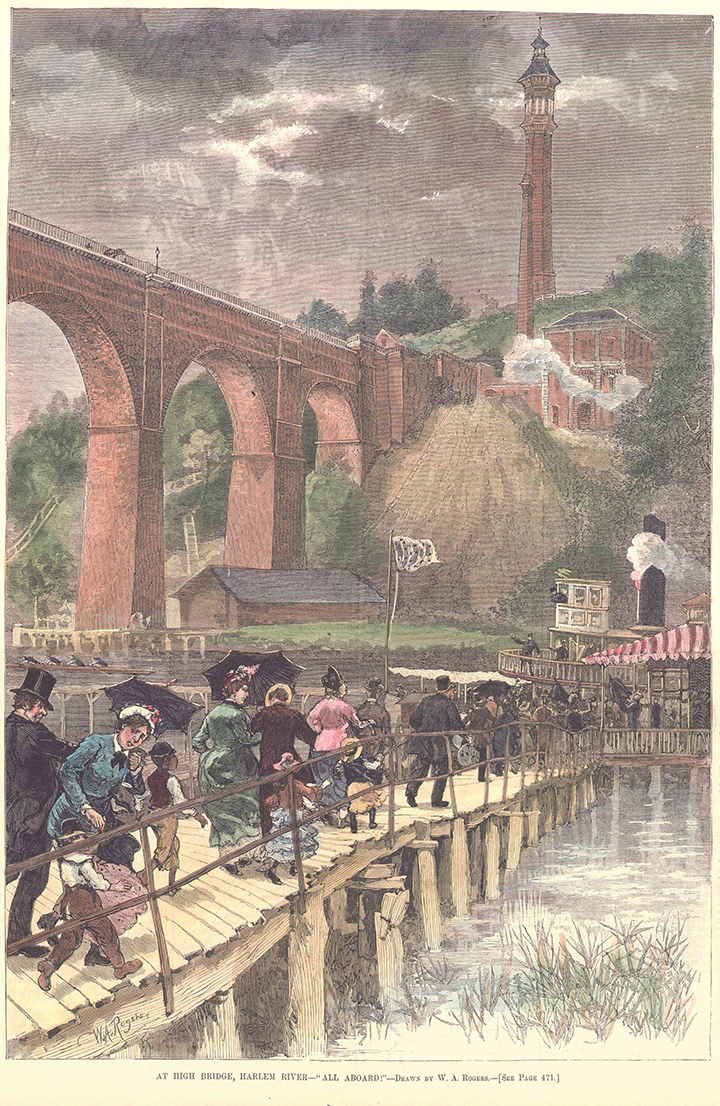

The older engravings, mostly of valley crossings, featured the magnificent structures John B. Jervis built to span the various brooks, rivers and valleys along the line of the aqueduct. In later prints, the imposing tower on the Manhattan side of the High Bridge makes its appearance, sometimes in the background of a bustling crowd of sightseers who throng the bridge or hurry to get on the steam excursion boat that will take them back to Lower Manhattan. Today, the High Bridge is closed, and Highbridge Park, built in the 19th century, is no longer a popular destination, although efforts are being made to rehabilitate the bridge and to reclaim the park.*

On May 7th, a group of aqueduct enthusiasts was gathered in an unprepossessing neighborhood of Spanish Harlem, at 173rd Street and Amsterdam Avenue, at the High Bridge Recreation Center where our guide, Professor Sidney Horenstein, was engaged in lively discussions as a prelude to the tour proper.

Setting off at a brisk clip toward the tower, we climbed a fairly steep grassy slope adjoining a ballfield. Some of the boys and young men, curious about our errand into their neighborhood, left their bats behind and joined the group. At intervals, Professor Horenstein would stop and give a brief talk. Witty, erudite and enthusiastic, he introduced himself as a person who works at the American Museum of Natural History during the day and roams the city's parks at night. His expositions on engineering, industrial archeology, history and art history were frequently interrupted by digressions on Manhattan's foundations, as he gave inspired mini-lectures on schist, gneiss and other rocks most laymen would hesitate to pronounce. Whenever we passed a boulder or outcropping, he would touch them with almost loving reverence. Primarily a geologist, he has an encyclopedic knowledge of all things relating to the city.

'At High Bridge, Harlem River - 'All Aboard!'" from Harper's Weekly, July 24, 1880. Note conical slag heap to the right of the bridge, below the powerhouse. (Courtesy of R. Kornfeld, Jr.)

From the plaza at the foot of the tower, we had a magnificent view across the High Bridge toward the Bronx. It was only now that I learned the true function of this marvelous edifice, built 30 years after the aqueduct's opening in 1842. It is a water tower into which the water from the aqueduct, flowing across the High Bridge, was pumped, lifting it to serve the apartment buildings rising on the heights of northern Manhattan. A large brick structure adjoining the tower, part of the same project, was the High Bridge Reservoir. The reservoir was rebuilt in 1934 as a community swimming pool.

As we climbed the spiral staircase of the tower, we could admire the two massive pipes in the center, the larger one for water being pumped to the top, the other for the downflow. We also noticed the beautiful brickwork, the charming little windows, the lacy ironwork of the staircase, and the solid overall construction.

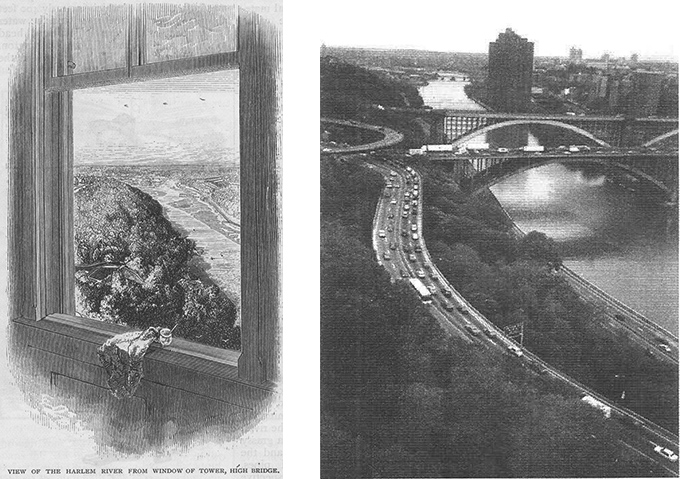

The lookout floor at the top, lit by tall windows around the perimeter, provides one of the most interesting 360-degree views of the city - unusual, as this is a rare overview of Manhattan's north end with which few of us were familiar. Bridges abound. The George Washington Bridge, with Pier Luigi Nervi's striking bus terminal at the Manhattan end, is nearby. So are the Alexander Hamilton Bridge and the Washington Bridge across the Harlem River to the immediate north. And, of course, the High Bridge, the oldest bridge connecting Manhattan with the mainland.

Some of the more adventurous among the group climbed even higher to explore a windowless chamber at the very top. The tower's huge wooden water tank is long gone. Vandalism and fire have done their work, and the graceful, slender tower no longer has its original crown; the cupola was reconstructed 12 years ago. The doors of the tower are now kept locked.

Other changes can be seen by comparing the tower's appearance today with late 19th century engravings. The High Service Works at the Manhattan end of the High Bridge encompassed not only the tower and reservoir but also a large powerhouse for pumping the water into them. The artists show black coal plumes and fumes belching forth from a tall chimney, and a monumental slag heap at the side of the powerhouse that sends slag cascading into the Harlem River - an environmentalist's nightmare. We later walked past the electrical pumping station on Amsterdam Avenue serving the New Croton Aqueduct. It emits a reassuring modern hum.

The tour concluded with a walk through the original Highbridge Park on the steep slopes toward the river. Designed with care and artistry by Calvert Vaux and Samuel Parsons, Jr., and built with the craftsmanship of an earlier age, it boasts stone paths, stairs, terraces, arches and grottoes, bordered by lovely iron fences. Although the plantings have disappeared and wild vegetation has taken over, and much of the masonry is defaced or in ruins, one can still derive a bittersweet pleasure from this monument to civic amenities of the past. Professor Horenstein spoke movingly about the vanished glory of this place. Many in our crowd wondered how many New Yorkers had ever visited here, or even know that it exists.

My love for the romance of the Croton Water has increased even more as a result of the tour. I do think of the Old Croton Aqueduct as the single greatest public achievement that made possible the growth of modern New York City. But I also learned that long ago, during the last ice age, New York City was at the glacier's edge, an end moraine. Ice advancing south embedded with pebbles carved rills on the bedrock surface, and left behind boulders, pushed from New Jersey, as it retreated.

Left: View of the Harlem River from High Bridge Tower, from Scribner's Monthly, Vol. 14, 1877. Right: The view today. (Photo by D. Ramsey)

The city's site thus was formed by huge forces of nature, but human imagination, ingenuity, intellect, and labor shaped and built and struggled and succeeded in creating a water system to support a civilized habitat for millions of people. The High Bridge Tower stands as a proud reminder of that accomplishment. As one of my friends from the Friends of the Old Croton Aqueduct suggested, it should have a beautiful banner flying from the top. Any ideas for a design?

*Note: The High Bridge reopened to the public in 2015 after a complete restoration. Conditions in Manhattan's Highbridge Park are greatly improved through major capital investments by New York City over several decades.