Histories of the Aqueduct often stop with the completion of its construction. This account gives an overview of the system's operation in the succeeding decades. - Ed.

The Old Croton Aqueduct was built out of desperation during an economic depression and without consensus on a long-term plan. There were jurisdictional disputes between the state and city, and there was no existing agency to which to tum over the completed aqueduct. The Water Commissioners had been appointed to build the aqueduct, not to operate it indefinitely.

A new Department. After the Aqueduct went into service in 1842, Chief Engineer John B. Jervis agreed to stay on part-time at half-salary for six years until the High Bridge was complete. Myndert van Schaick, who had been the prime mover in the decision to build the Croton Aqueduct back in the early 1830s, stepped in to head Aqueduct operations in 1848 when the Water Commissioners turned over the completed works to the city. He organized the Croton Aqueduct Department, which was inaugurated in 1849. Alfred W. Craven was appointed Chief Engineer, a position to which he dedicated his life for 20 years.

The Croton Aqueduct Department was governed by a three-man board, which included the Chief Engineer. There were two Assistant Engineers, one of whom was the Resident Engineer. The 41-mile-long Aqueduct was divided into eight divisions and a Superintendent assigned to each. (James Bremner, who lived and worked in the Overseer's House in Dobbs Ferry, was Superintendent of the Fourth Division.)

There was also a Keeper for the Murray Hill Reservoir and originally a Keeper for the Croton Fountain in City Hall Park as well. Other engineering personnel such as construction inspectors, and workers like masons and laborers, were paid hourly and not listed as department employees.

Unbridled growth. When the Aqueduct was designed in the 1830s it was not expected that the city's population would reach one million within a century. The planners had used an assumption of 20 gallons per day per capita. In fact, people started using 90 gallons per day per capita after the Croton Aqueduct Department built sewers throughout the city. Before sewers were installed there was nowhere for wastewater to go, especially in low-lying neighborhoods - the Croton River threatened to turn the city into a swamp!

To accommodate the city's unbridled population growth in the mid-19th century, the Aqueduct was operated way beyond its original design capacity. Modifications were made to reinforce the top arch and buttress embankments, but the Aqueduct was still overstressed.

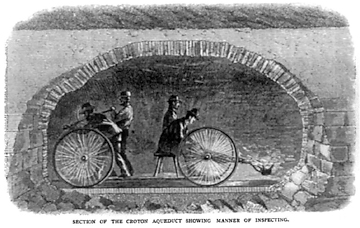

By the 1870s, each Superintendent was required to inspect the masonry along his entire division of the aqueduct twice each day. This was an exterior inspection done on foot or horseback to look for cracks and leaks. Repairs, except for the worst emergencies, had to be done without shutting off and restarting the water (a procedure that took days). There was a planned shutoff for an annual inspection, a grand procession through the aqueduct tunnel of the Chief Engineer and his assistants, followed by a frenzy of repair work.

To conserve water, the supply leaving the reservoir in Central Park was restricted to prevent the water going out faster than it came in. Low pressure deprived many upper-floor apartments of service entirely. When there was a fire, the Superintendent of the Central Park Reservoir was immediately telegraphed. He would open the gates to increase pressure for firefighters' hoses.

A stressed system. Benjamin Silliman Church, Resident Engineer of the aqueduct for over 22 years, spoke to the Westchester County Historical Society in 1882. He described the maintenance of the Aqueduct Benjamin S. Church during this critical period: "Leaks began to appear, frequently gushing forth suddenly, and threatening serious consequences."

Lobbying for construction of the New Croton Aqueduct, Church went on to describe the dangers of operating the Old Croton Aqueduct at its maximum capacity:

"A sudden rise in the Croton Lake, unless watched by the keeper having charge of the gates, might prove just the excess of pressure it was powerless to bear; and should six inches or a foot more water enter the aqueduct, and cause the arch on the weakest embankment near Tarrytown to give way, and fall in, such sudden check to the flow, and backward pressure, would occasion a shock which would throw down the roof-arch of the aqueduct on the embankment above, and in this manner they would fall in, one after the other, like a row of bricks, all the way back to Croton Dam.

" ... This is not just a theoretical danger .... On one of these occasions of a sudden rise such a disaster was prevented by the keeper, who, by chance, made an unusual midnight inspection, and found the watchman soundly sleeping, with an empty whiskey bottle beside him."

Until the New Croton Aqueduct went online in 1890, there was no alternate source of water in case of such a collapse. As Church stated in the same address, "New York City would have been reduced to extremities that imagination fails to depict."