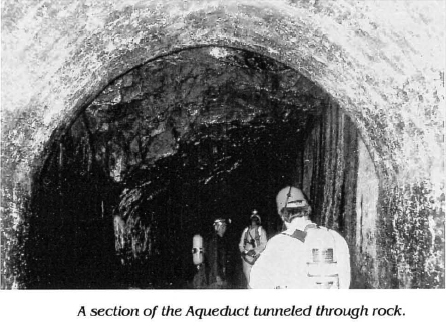

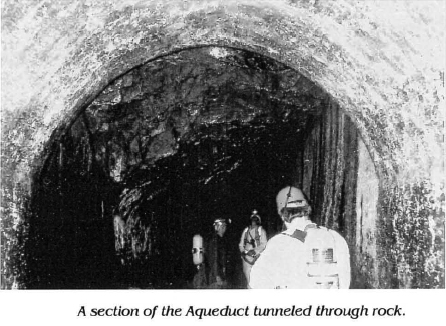

Have you ever wondered what it's like inside most of the Aqueduct, the part that hasn't been cleaned, polished, and ventilated for visits by the public? Trail Manager Brian Goodman offers a glimpse.

When the Aqueduct was fully in use, engineers conducted regular inspections of the inside of the structure, at least twice a year by boat, a journey not for the faint-hearted. When maintenance was required, the water now was cut off completely by lowering the gates in the waste weirs. Today, our inspections are normally geared to specific projects such as proposed construction nearby, particularly when blasting is contemplated, to ensure "before and after"' that no damage has occurred.

Entry procedures are complicated. Federal regulations require that anyone entering confined space be trained and qualified and that a Confined Space Rescue Team be on site. Last fall, engineering consultants, park staff and the regional rescue team walked one and a half miles up to the 8-foot concrete "plug" which seals off the conduit in Ossining. This was installed in 1989 when the northern sections returned to use as a contribution to the community's water supply. In addition to the main task of inspecting the tunnel under the GE Management Institute, we took the opportunity to record and photograph the effects of time, weather, and above-ground construction.

In one section, the roof descended 19 inches below its customary 8-1/2 feet and our immediate concern was that a century of traffic at a crossing under Route 9 was finally affecting the structure. A measuring wheel is a necessary item of equipment and, on repeating the trip on the surface the following morning, it transpired that the section in question was comfortably distant from the main road. A thorough inspection of the trail surface, the outer "rip rap" retaining wall, and an original stone culvert running under the Aqueduct revealed no sign of subsidence. The conclusion was that the lowered roof was part of the original design.

The northern sections are also inspected periodically. Access is via ports in the roof of the tunnel after some 6 feet of trail surface and the concrete caps are removed by a back-hoe. The Aqueduct is emptied of water, the gate valves at the New Croton (Cornell) Dam are "locked and tagged" for safety, explosion-proof lighting is installed, a continuous flow of fresh air pumped in, strain gauges placed over small cracks in the brickwork, and any necessary patching conducted.

Elsewhere, some sections remain in excellent condition. Others show wraithlike tree roots penetrating the walls, hardened "waterfalls" of white, brown and scarlet caused by leaching minerals, ceramic plaques marking the numbers of the original survey stations and even raccoon footprints in the mud.

Other tunnel exercises by the Confined Space Rescue Team have taken us into the weir at the Pocantico River crossing, past Bell Atlantic telephone cables in Irvington, and to the site of the piers for the new bridge in Archville, where an eel swam unconcerned in the inverted Siphon under Route 9. Such findings add an element of mystery to our daily round.